Two China Questions

In this issue of Sinology, Andy Rothman offers his perspective on two key questions.

Key Takeaways

- Chinese economy is in decent shape this year. Not fantastic, but still one of the strongest in the world.

- There are problems, especially in the property market, and confidence is weak. But, at some point in the near future, I believe Xi Jinping will follow in his predecessors’ footsteps and make the pragmatic course corrections that will revitalize China’s entrepreneurs and consumers.

- Regardless of who wins the U.S. elections in November, the political relationship between Washington and Beijing will remain tense. Tariffs and export controls will probably proliferate.

- But, the impact on China’s economy isn’t likely to be as severe as many expect, because it’s a domestic-demand driven economy

There are two important questions investors should be asking about China. First, the Chinese economy is doing fairly well, so why are Chinese entrepreneurs and households so pessimistic, and what could turn that around? Second, will the political relationship between Washington and Beijing remain tense after the U.S. elections, and how much will that matter to the Chinese economy? In this Sinology, I offer my perspective on both questions.

I. The Chinese economy is doing fairly well, so why are Chinese entrepreneurs and households so pessimistic, and what could turn that around?

Media coverage is so downbeat that investors may not realize that the Chinese economy is in decent shape this year. Not fantastic, but still one of the strongest in the world. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), for example, forecasts GDP growth of 4.6% in China in 2024, second only to India (6.8%) among major economies, and compared to 2.7% for the U.S., 0.8% for the Euro Area, and 0.9% for Japan.

According to Bloomberg calculations using IMF forecasts, China will account for 21% of global economic growth over the next five years, larger than the share of all G-7 countries combined. (India will account for about 14% of global growth through 2029, according to Bloomberg, with the U.S. at 12% and Japan about 2%.)

In the first quarter of this year, inflation-adjusted (real) per capita household income in China rose 6.2% year-over-year (YoY), after increasing 21% in 2023 compared to pre-pandemic 2019. Retail sales rose 5.2% YoY in real terms in the first quarter, after a 16% expansion last year compared to 2019.

Real per capita household consumption rose 8.3% YoY in 1Q24, compared to 4.1% a year ago and 5.4% in pre-pandemic 1Q19. In each of the last five quarters, after the end of zero-COVID restrictions, household consumption grew faster than income, signaling strong domestic demand.

Electricity consumption, a proxy for economic activity, rose 9.8% YoY in the first three months of the year, after increasing 26% last year vs. 2019.

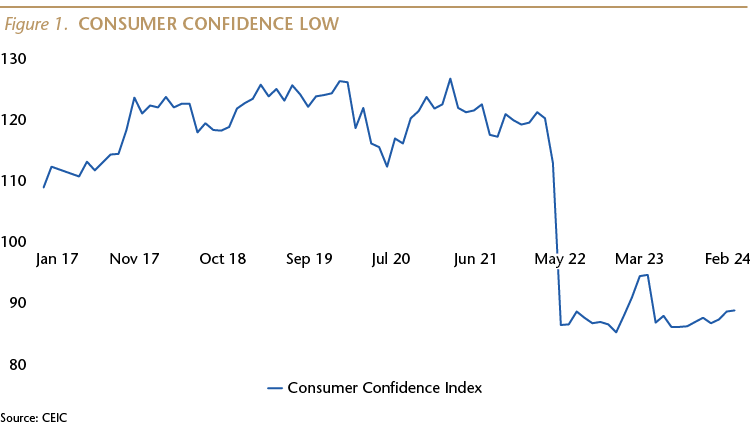

Despite these decent growth rates, the consumer confidence index hasn’t recovered from its collapse in April 2022, when more than 20 million Shanghai residents were locked down during a COVID outbreak. The index ticked up a bit after the end of zero-COVID restrictions in late 2022, but quickly fell back and has remained at the lowest levels since the survey, by the National Bureau of Statistics, began three decades ago.

In my view, confidence has remained very weak due to four factors. 1) Chinese entrepreneurs fear that Xi Jinping has fallen out of love with private firms, where most consumers work; 2) poor execution of well-intentioned policies, such as common prosperity, has left entrepreneurs reluctant to hire and invest; 3) policy mistakes have led to a collapse in the housing market, with significant spillover to many industries and consumer sentiment; and 4) many in China worry that the deterioration in political relations with the U.S. will slow economic growth or lead to conflict.

Let’s take a look at these four issues:

Private sector jitters

In 1984, when I first worked in China, as a junior American diplomat, there were no private companies—everyone worked for the state. Today, almost 90% of urban employment is in small, privately owned, entrepreneurial firms. Private companies are also responsible for most innovation and wealth creation in China.

The private sector continued to thrive during Xi’s first 10 years as head of the Chinese Communist Party, but recently, many entrepreneurs have worried that Xi’s attentions have been focused more on the smaller, state-controlled part of the economy. These concerns have been driven in part by Xi’s rhetoric, and also by some of his policies, which have created a chaotic and untransparent regulatory environment for private companies. This has made entrepreneurs reluctant to hire and invest.

Poor policy execution

In recent years, Xi announced a series of policies which were intended to address the same socio-economic concerns that most democracies are wrestling with, from income inequality to unequal access to education and health care. Unfortunately, implementation of these policies was often poorly managed. Policy objectives were not accomplished, and unintended consequences damaged commercial activities and entrepreneurial confidence.

A storm of regulatory changes roiled many parts of the Chinese economy, crashing the property market, shutting many after-school tutoring businesses, pausing the launch of online games, and creating electricity shortages.

Housing market collapse

One of the most significant policy implementation mistakes was the government’s attempt to cool off the residential property market. Restrictions on bank lending to developers in 2020, referred to as “the three red lines,” inadvertently led to a collapse in new home sales, with spillovers into construction-related industries and damage to consumer confidence.

In the 25 largest cities, new home sales, on a square meter basis, fell 47% YoY in the first quarter. Many major developers are in serious financial distress, and it is estimated that new home prices have fallen about 15 to 20% from their 2021 peak.

Most new homes in China sold on a pre-sale basis, which means buyers put down 30% cash and immediately begin servicing their mortgage, while builders pledge to use those funds to complete construction, usually within 18 to 24 months. Recently, however, many developers have failed to meet their contractual obligations, and we estimate that more than 7 million buyers are still waiting to receive their pre-paid apartments, with little recourse.

It is, however, important for investors to remember the context for China’s current property woes. The property sector’s contribution to overall economic growth has been declining for many years as China’s housing market has matured. The compound annual growth rate (CAGR) for new home sales was 23% for the period 2001-2007, then 10% for 2008-2010, then 7% from 2011-2017, and down to 2% during 2018-2021. After the government restricted bank lending to developers, new home sales fell 34% YoY in 2022, and then fell another 8.2% YoY in 2023. Despite this deceleration, and COVID, China’s GDP expanded at an average annual pace of 6.2% over the last 10 years.

It is also important to recognize that homeowner leverage is much lower in China than in the U.S.—a factor that helps to limit the overall impact of falling prices. In China, the minimum cash down payment for a new flat is 20% of the purchase price, and the average is 30% down—far from the median cash down payment of 2% ahead of the U.S. housing crisis. And, surveys tell us that about 90% of new homes in China are sold to owner-occupiers. Few, if any, homeowners should be underwater on their mortgages.

U.S.-China tensions

Over the course of several post-COVID trips to China, it was clear that many Chinese are also worried about the deterioration in the political relationship between Beijing and Washington. While domestic issues are the primary source of weak confidence, concerns about the bilateral relationship have compounded the problem. I will address this in detail in the second section of this report.

A pragmatic course correction is likely

I do expect Xi to fix these problems with pragmatic policy changes, but that course correction has not yet begun, and there is no way to predict when the changes will take place. It is likely that the relatively strong first quarter economic results will postpone the arrival of necessary policy changes.

I am, however, confident that these changes will come because Xi knows that pragmatic economic policies supporting entrepreneurs have made China rich and kept the Party in power, and at some point he will recognize that without another course correction, the economy isn’t likely to grow fast enough to support his ambitions for the country.

In 1980, when I first visited China as a student, its per capita GDP was less than that of Afghanistan, Haiti and Bangladesh, and 80% of China’s population was living below the World Bank’s poverty line. In recent years, because of its entrepreneurs, China accounts for about one-third of global economic growth, larger than the combined share of global growth from the U.S., Europe and Japan.

“The Chinese transformation is a unique event in world economic history: never have so many people over such a relatively short period of time increased their income so much,” according to a 2020 study by economists Branko Milanovic, Filip Novokmet and Li Yang. They found that “it took the UK about a century-and-half to increase its GDP per capita by half as much as China did in less than 40 years” and “it took the United States 240 years. . . do what China accomplished in 40 years.”

How was this boom achieved? “The answer is straightforward,” according to economist Barry Naughton. “Market-oriented economic reforms are what actually shaped development.”

The rise of China’s private sector has largely continued under Xi Jinping. Since he became head of the Party in 2012, private firms have continued to drive all net, new job creation. Real income growth has risen at an average annual pace of 6.3%, compared to 1.7% in the U.S. and 1.0% in the UK. China’s per capita GDP, on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis, was 28% of the U.S. in 2022, up from 19% in 2012. Entrepreneurial, privately owned companies have fueled this growth.

Xi has said he wants to “enhance the ability to get rich,” and that “small and medium-sized business owners and self-employed businesses are important groups for starting a business and getting rich.” Xi said, “It is necessary to protect property rights and intellectual property rights, and protect legal wealth.”

I expect Xi to follow in the pragmatic footsteps of his predecessors. In 1992, following a period of high inflation and unemployment, Deng Xiaoping embarked on a tour across southern China to promote the country’s nascent private sector, stating that “Whoever is against reform must leave office.” A long period of double-digit GDP growth followed.

Ten years later, Jiang Zemin kick-started another period of strong growth by welcoming entrepreneurs into the Communist Party.

Xi needs to make his own version of Deng’s famous 1992 southern tour, providing rhetorical support for entrepreneurs, promising (and delivering) a more transparent regulatory environment for private firms, and restoring credit lines to healthy developers.

Saving for a recovery in confidence

Since the beginning of 2020, family bank balances have risen 79%, a net increase equal to US$ 9.1 trillion, which is much larger than the GDP of Japan in 2022, and equal to 95% of the China’s tradable A-share market capitalization at the end of March 2024.

Total household bank deposits have hit a new record, equal to US$20.6 trillion as of the end of March 2024, which is equal to 75% of the U.S.’ 2023 GDP.

Once confidence returns, this savings could be significant fuel for a continuing consumer spending rebound, as well as a recovery in mainland equities, where domestic investors hold about 95% of the market.

II. Will the political relationship between Washington and Beijing remain tense after the U.S. elections, and how much will that matter to the Chinese economy?

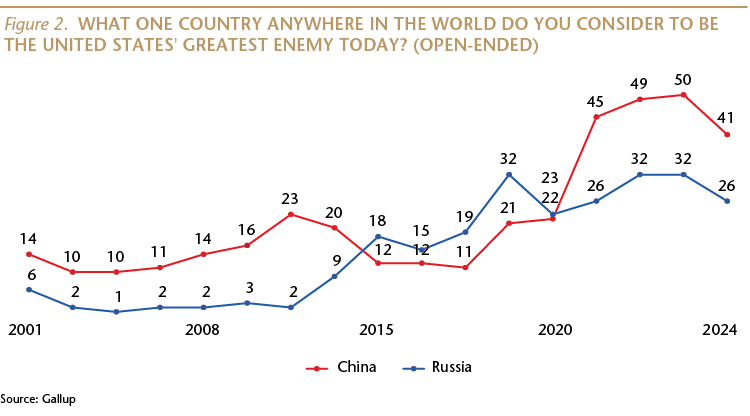

One of the very few things politicians from both American political parties agree on is that China is the greatest threat to the U.S., so it is very likely that the bilateral relationship will remain very tense in the coming years, regardless of who wins the November elections.

Many Americans agree that China is a threat, although it is likely that those views have been influenced by the increasingly heated rhetoric from politicians. In 2012, for example, the percentage of Americans polled by Gallup who said China was the U.S.’ “greatest enemy” jumped to 23% from 16% the year before, when, according to the Pew Research Center, the “presidential election was marked by the two candidates [Obama and Romney] competing over who would be tougher on China if elected.”

This year, with China again a leading campaign issue, 41% of Americans polled by Gallup say that China is the “greatest enemy” of the U.S., compared to 26% who chose Russia. While the share citing China as America’s top enemy is down from 50% last year, the 41% level is dramatically higher than the 14% in 2001, when China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO). In a 1983 Gallup survey, which asked a different question, only 3% of Americans described China as an “enemy.”

One explanation for this shift in attitudes towards China (in addition to more aggressive behavior by Beijing) is that Americans are increasingly more insecure about their own future. In a Gallup poll conducted in March, 75% of American respondents said they are dissatisfied “with the way things are going in the U.S. at this time.”

I recall a similar phenomenon during and immediately after the U.S. recessions of the early 1980s, when rising unemployment was blamed on unfair Japanese competition, and anti-Japanese sentiment rose. In a 1980 poll, only 12% of Americans had an unfavorable attitude towards Japan, but that share jumped to 29% two years later. According to historian Michael Heale:

For many Japan was the greatest threat to the U.S. With the crumbling of the Soviet bloc there was a growing conviction that a country’s international status would be determined by its economic power, and it was the Japanese economy rather than the American that now appeared to be performing miracles . . . apprehensions over a new Yellow Peril eventually commanded considerable public attention and began to infiltrate popular culture.

CIA director William J. Casey characterized Japanese investment in American computer companies as “a Trojan horse” [and] a 1991 book entitled The Coming War with Japan . . . anticipated a bloody military conflict.

While politicians generally agree on the China threat, American perceptions do vary by party affiliation. In this year’s Gallup survey, 67% of Republicans chose China as the U.S.’ “greatest enemy,” compared to 18% of Democrats. This difference was presumably in part due to the way political leaders talk about Putin’s invasion of Ukraine: Only 10% of Republicans chose Russia as the greatest threat, while 48% of Democrats said Russia was the top enemy.

Nonetheless, politicians from both parties are focused on China.

In an era when votes on most federal legislation are divided along party lines, the House of Representatives passed a bill that would lead to a ban of the popular video app TikTok by a vote of 352-65.

And anti-China sentiment is common outside of the Beltway as well. Over two-thirds of state legislatures have enacted or are considering laws which would limit or ban Chinese ownership of land. This, despite the U.S. Department of Agriculture reporting that Chinese citizens own only 0.03% of all privately held farmland in the country, and U.S. intelligence agencies have not publicly reported any espionage cases related to that land. One of the largest Chinese landowners is Smithfield, the largest pork producer in the U.S.

In Florida, a law signed last May by Governor Ron DeSantis would, according to the American Civil Liberties Union, bar most Chinese citizens from purchasing homes in the state. A lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the law has been supported by the U.S. Department of Justice, which says the “property ownership restrictions violate the Fair Housing Act because they discriminate based on a person’s national origin and violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because the restrictions are not narrowly tailored to serve any compelling government interest.”

Inside the Beltway, both parties have been busy with anti-China rhetoric and legislation. We can look at this to anticipate how Joe Biden and Donald Trump might manage the U.S.-China relationship in a second term.

Biden is running as a careful China hawk

President Biden has kept in place the tariffs on Chinese goods enacted by then-President Trump, and he has taken a number of steps to escalate trade barriers with China.

According to Bloomberg, Biden has put more Chinese companies (319) on export blacklists than were added during the Trump administration (306).

The Biden administration also announced its intention to replace the more than 200 Chinese-made cranes operating in U.S. ports, despite not providing evidence that these have been used for nefarious purposes, as well as the absence of any U.S.-made alternatives. The administration has also not explained why the U.S. private sector and national security agencies are unable to take measures to prevent Chinese-made cranes from potentially becoming a security threat.

Similarly, Biden’s Secretary of Commerce has said that Chinese-made electric vehicles (EVs)—none of which are currently operating on American roads—are a national security threat because they are “collecting a huge amount of information about the driver, the location of the vehicle, the surroundings of the vehicle.” Members of Congress have called for bans on Chinese EVs from being sold in the U.S., with Senator Sherrod Brown, an Ohio Democrat, calling Chinese-made EVs an “existential threat to the American auto industry.”

At an April campaign rally in Pennsylvania, Biden proposed tripling the current tariffs on Chinese steel imports. The economic and national security rationale for this is questionable, given that last year, imports from China accounted for about 2% of total U.S. steel imports by volume, and only about 0.6% of total U.S. steel consumption.

Jake Sullivan, the president’s national security advisor, has said these steps are justified because the administration has “determined that the PRC was the only state with both the intent to reshape the international order and the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to do it.”

Biden, is, however, trying to be a careful China hawk, saying, “I’m not looking for a fight with China. I’m looking for competition—and fair competition.”

Over the past 12 months, a steady resumption of senior-level engagement between Washington and Beijing, including a meeting in California between Biden and Xi, has in fact stabilized the political relationship. American officials report tangible progress on key issues, including tighter controls over the production in China of precursor chemicals used in making fentanyl, and resumption of dialogue between military leaders.

According to the Financial Times, since the two leaders met, Chinese fighter jets have stopped dangerous maneuvers around U.S. spy planes operating near China.

In a second Biden administration, we can expect a continuation of this approach to China that mixes tariffs intended to placate American labor unions, with export controls designed to constrain the development of China’s tech sector, along with diplomatic engagement to prevent those measures from turning tensions into conflict.

Trump could be transactional or more hawkish

In addition to sharply raising tariffs on Chinese imports as president, Trump has a long history of critical comments about China.

In a 2016 campaign rally, he said, “We can’t continue to allow China to rape our country, and that’s what they’re doing.”

A 2020 White House statement declared, “For decades, Donald J. Trump was one of the few prominent Americans to recognize the true nature of the Chinese Communist Party and its threat to America’s economic and political way of life.”

But, Trump has sometimes taken a somewhat more constructive approach. In his 2020 State of the Union address, he said, “For decades, China has taken advantage of the United States. Now we have changed that, but, at the same time, we have perhaps the best relationship we’ve ever had with China, including with President Xi. They respect what we’ve done . . .”

Recently, however, some in Trump’s orbit have been more confrontational. Mike Johnson, Speaker of the House of Representatives, in mid-April said, “I believe Xi, Vladimir Putin and Iran really are an axis of evil.”

Mike Pompeo, Secretary of State under Trump, in 2022 called for the U.S. to abandon its longstanding one-China policy and grant Taiwan “diplomatic recognition as a free and sovereign country,” a move that would almost certainly spark conflict. Hawkish language about Taiwan from many in Trump’s circle may lead to an elevated risk on what has always been the most sensitive issue in U.S.-China relations.

Robert Lighthizer, Trump’s trade representative and a candidate for another top job if Trump wins in November, published a book last year titled, “No Trade Is Free: Changing Course, Taking on China, and Helping America’s Workers.”

Lighthizer, who appears to continue to be close to Trump, wrote that a “great contribution” of his presidency “was to awaken the country and ultimately the world to the danger of our growing economic dependence on China. China is an adversary of the U.S.”

In his book, Lighthizer says, “some think it is okay for us to send hundreds of billions of dollars to China for televisions and other consumer goods,” but, “a nation cannot treat its chief geopolitical adversary as just another market participant.”

Calling China “the greatest threat that the American nation and its system of Western liberal democratic government has faced since the American Revolution,” Lighthizer says, “If we lose this confrontation, the world will be a very different place. This is a life and death issue. Our very way of life—and the fate of the free world as such—is at stake.”

Lighthizer, of course, helped Trump implement tariffs of as much as 25% on many imports from China. A study by economists at the New York Fed, Columbia and Princeton Universities, found that those tariffs “were almost completely passed through into U.S. domestic prices, so that the entire incidence of the tariffs fell on domestic consumers and importers up to now, with no impact so far on the prices received by foreign exporters. We also find that U.S. producers responded to reduced import competition by raising their prices.”

Another study, published by the Federal Reserve Board, concluded that “the 2018 tariffs are associated with relative reductions in manufacturing employment and relative increases in producer prices.”

Trump, however, in a February 2024 interview, suggested that if he is elected, he would put a tax of more than 60% on goods from China, a move that would likely have even greater impact on U.S. consumers, domestic prices and employment.

It is possible that in a second term, Trump could return to the transactional mode that led, in December 2019, to his “very large Phase One Deal with China,” which he called a “tremendous victory for the American economy.”

But, it’s not clear that Trump would want to move in that direction, and it is also not clear that Beijing would be willing to engage in that kind of negotiation, given how tense the bilateral relationship has become over the last four years.

The relationship will remain tense, but the impact on China’s economy will be limited

Whether Biden or Trump return to the White House next year, U.S.-China relations are likely to remain tense. Tariffs and export controls will probably proliferate.

But, the impact on China’s economy isn’t likely to be as severe as many expect.

China is domestic-demand driven

One reason some investors are too pessimistic about the impact of U.S.-China tensions is that they overemphasize the role of trade in China’s economy.

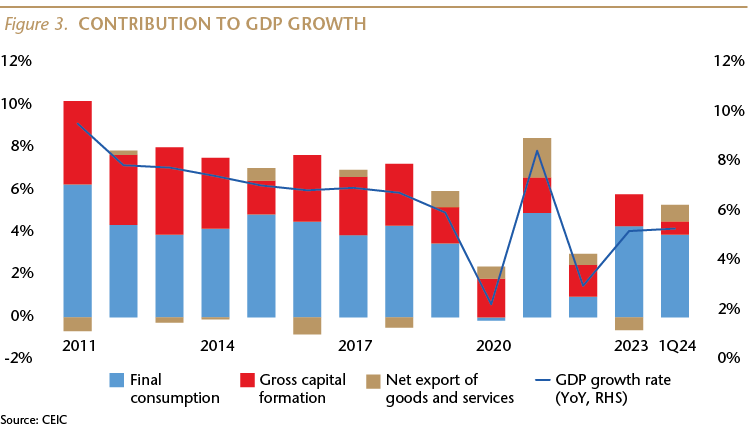

Economists focus on net exports, the value of a country’s exports minus its imports (because GDP measures domestic production). The net export share of China’s nominal GDP peaked at 8.7% in 2007 and was only 1.8% in 2017, before the Trump tariffs. In 2019, net exports accounted for 1% of China’s GDP, compared to 6% in Germany.

Another way to look at it is that in 2023, 83% of China’s GDP growth came from final consumption, and net exports were a -11% drag on growth.

With the Biden administration criticizing Beijing for promoting exports over domestic demand, it’s worth noting that in the first quarter of this year, final consumption accounted for 74% of GDP growth (up from 66% in 1Q19). Net exports contributed 15% of GDP growth, down from 21% in 2019. (The balance, of course, came from gross capital formation.)

All of this adds up to a conclusion that American measures to stymie China’s exports are unlikely to have a dramatic impact on China’s economy, which is primarily driven by domestic demand.

It’s also worth remembering that there are plenty of other markets available for Chinese goods, and many of these are more receptive to made-in-China. Last year, 29% of China’s exports went to the more developed G-7 markets, down from a 48% share in 2000. This more than compensated for the impact of the Trump tariffs, which meant that last year, 15% of China’s exports went to the U.S., down from 19% in pre-tariff 2017.

Moreover, a new study by the Federal Reserve Board found “that the increased tariffs have led to a shift in U.S. imports from China to U.S. imports from other trading partners. But we also find that the trading partners that the U.S. had shifted to are importing more from China precisely those goods that the U.S. is importing less of from China. Thus, indirect reliance on China may have fallen less than direct reliance as measured by trade flows.”

This explains why China’s share of global exports was 14% last year, up a bit from 13% before the Trump tariffs.

If China’s leaders make the pragmatic course corrections we discussed in the first section of this report, a stronger domestic economy would likely outweigh any headwinds from tensions in the U.S.-China relationship.

Tech restrictions bark might be worse than bite

A second reason some investors are too pessimistic about the impact of U.S.-China tensions is related to export controls.

It is likely that either a Biden or Trump administration will continue to ratchet up restrictions on the export of advanced technology to China. But, it’s also likely that the impact of these restrictions will be less dramatic than many fear.

A new study by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that these export controls may hurt American tech firms as much or more than those in China. The study found evidence of “broad-based decoupling from China” by U.S. suppliers, who found it difficult to quickly find alternative customers, which “may therefore harm the very same firms whose technology U.S. export controls are trying to protect.”

“Our estimates suggest that export controls cost the average affected U.S. supplier $857 million in lost market capitalization, with total losses across all the suppliers of $130 billion.” The Fed study added that there is “real collateral damage from export controls,” in terms of declining revenue, profitability and employment.

On the Chinese side, the Fed reported: “Moreover, the benefits of U.S. export controls, namely denying China access to advanced technology, may be limited as a result of Chinese strategic behavior. Indeed, there is evidence that, following U.S. export controls, China has boosted domestic innovation and self-reliance, and increased purchases from non-U.S. firms that produce similar technology to the U.S.-made ones subject to export controls.”

Paul Triolo, who has 30 years of experience covering China’s technology rise, in the U.S. government and private sector, reached a similar conclusion in an article published in February:

At the end of the day, however, the U.S. approach to export controls—the belief that preventing Chinese firms from accessing key U.S. and allied-country technology will prevent Chinese companies from doing certain things—will founder on the rocks of reality. The underlying problem of U.S. export controls is that we are dealing with applied science, and there is no single path to achieving technological performance levels, only many different, albeit difficult paths. Chinese firms will find the paths that work well enough to continue to drive innovation.

The impact of the U.S. ap¬proach to export controls in general, and on Huawei in particular, will likely mean that major U.S. and other foreign toolmakers are increasingly squeezed out of the Chinese market—U.S., Dutch, and Japanese tool¬makers are already among the biggest losers from export control policies targeting Chinese semiconductor firms like SMIC, YMTC, and CXMT.

Concluding comments

This is a great time for to be asking questions about China, because what happens in China continues to have a big impact on other economies and on many multi-national companies.

For the two key questions I discussed in this issue of Sinology, the consensus view is often, in my view, overly pessimistic.

Chinese economy is in decent shape this year. Not fantastic, but still one of the strongest in the world.

There are problems, especially in the property market, and confidence is weak. But, at some point in the near future, I believe Xi Jinping will follow in his predecessors’ footsteps and make the pragmatic course corrections that will revitalize China’s entrepreneurs and consumers.

Regardless of who wins the U.S. elections in November, the political relationship between Washington and Beijing will remain tense. Tariffs and export controls will probably proliferate.

But, as we’ve explained, the impact on China’s economy isn’t likely to be as severe as many expect.

Andy Rothman

Investment Strategist, China Macro

Matthews Asia

As of March 31, 2024, accounts managed by Matthews did not hold positions in Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), Yangtze Memory Technologies Co. (YMTC) and Changxin Memory Technologies (CXMT).

The Group of Seven (G-7), which includes Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States, has met regularly since the mid-1980s at the finance minister and central bank governor level.

China’s consumer confidence index is based on a survey of consumers, which includes questions about their current financial situation, their expectations for the future, and their spending intentions.