Sinology: On the Ground in China

Andy Rothman provides a first-hand perspective from his first trip to Shanghai and Beijing since the start of COVID in 2019.

Key Takeaways

- Two weeks on the ground in China made clear that people there are living with COVID just as we are, and that life on the streets, and in offices, bars and restaurants is consistent with macro data showing a gradual, consumer-led recovery.

- Life, and the economy, are clearly not yet back to pre-pandemic levels, but the process is well underway and is sustainable.

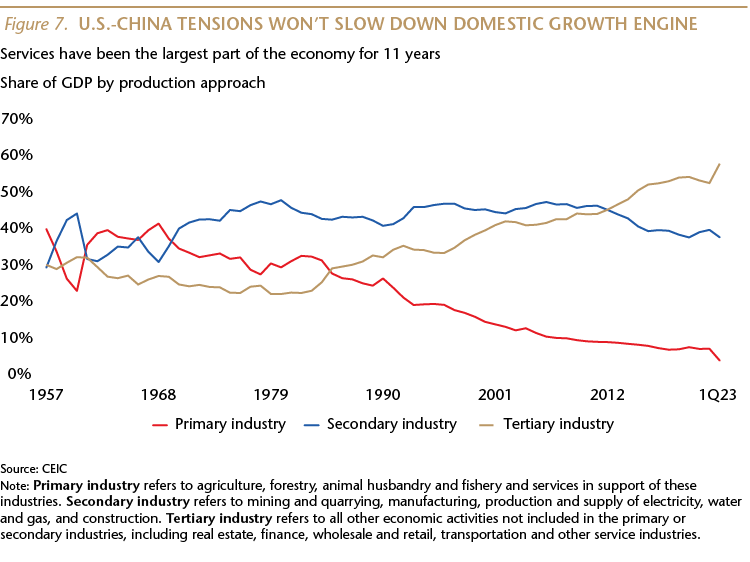

- The political relationship between Washington and Beijing is likely to remain strained, but a crisis is unlikely. Political and trade tensions won’t disrupt the Chinese economy, as domestic demand is its primary growth engine.

My first trip to Shanghai and Beijing since the start of the pandemic provided an opportunity for a first-hand checkup of China’s nascent economic recovery. My clinical assessment: the gradual, consumer-led rehabilitation is well underway and is likely to continue. The resilience of China’s entrepreneurs and pragmatic government policies should overcome the short-term challenges of weak manufacturing, low private-sector investment, and high youth unemployment. The property market has bounced back better than I’d expected. But, investors should anticipate that the road to rehabilitation will continue to have peaks and valleys, and that periods of softer data will lead some to prematurely proclaim the end of the recovery process.

Back on the ground

My last, pre-COVID trip to China was in December 2019, so it has been great to get back on the road again this year. In February, I returned to Taipei, Hong Kong and Shenzhen, and last month I was finally able to make an extended trip to Shanghai (where I lived for 14 years) and Beijing (where I lived for 5 years).

My first impression was that Chinese people are living with COVID just as we are. There are new cases, and I had to do one meeting by phone rather than in-person, with a contact who was recovering from a mild case, but no one was changing their behavior and there were no government COVID restrictions. Face masks were not mandatory, and only about two-thirds of passengers on the Shanghai subway were wearing them. There was no talk of resuming mass testing or the use of lockdowns. This was a big change from February, when masks were required everywhere I went in Asia, and I had to take a PCR test to travel from Hong Kong to Shenzhen.

My second impression was that life on the streets, in office buildings, bars and restaurants was consistent with macro data showing a gradual recovery in consumer activity and spending. Life—and the economy—are clearly not yet back to pre-pandemic levels, but the process is well underway.

The recovery continues, and is ahead of my expectations

I’m sure you’ve read reports of the early demise of China’s post-COVID recovery. One May headline in the Financial Times said that “China’s economic recovery is in doubt,” and the paper ran a column titled, “‘Boomy’ talk about the Chinese economy is a charade,” with the writer citing the “dim reality on the ground.”

I don’t know what ground that author walked on, but my path in Shanghai and Beijing was optimistic, rather than dim. Moreover, I’m not aware of any forecasts for the “reopening boom” mentioned in that column.

The recovery so far is actually ahead of my expectations. In a December 14, 2022 Sinology, I wrote that “I expect the macro data to remain weak in the first half of 2023, before a gradual recovery begins in the spring.”

I don’t think anyone expected the post-COVID recovery to be vertical or without fits and starts. The exceptionally strong March data—which we wrote about in the April 20 Sinology, “China’s Consumers Get Their Mojo Back”—probably reflected a one-time release of pent-up demand for everything that was out of reach during the time of zero-COVID. April—and probably the coming months—was a bit cooler, but this is not a reflection of the recovery hitting a wall.

Consumers shrugging off COVID trauma

Nothing I saw in Shanghai and Beijing conflicts with what I wrote in April: “China’s economy is in the early stages of a gradual, consumer-led recovery that is likely to be sustained by accommodative government policy and large household savings.”

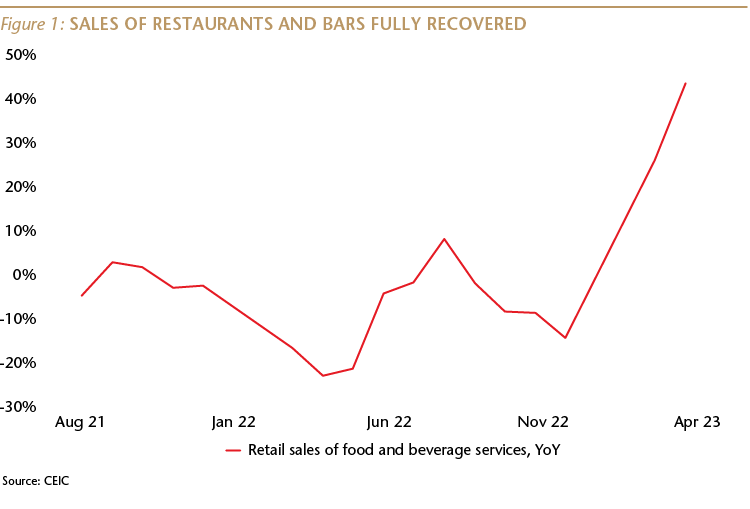

Restaurant and bar sales remained exceptionally strong in April, which I think is an important signal that Chinese consumers have begun to shake off last year’s COVID trauma. Sales at restaurants and bars rose 44% year-over-year (YoY) in April, up from a 26% growth rate in March, and compared to a decline of 23% YoY a year ago.

And this is not just the result of a weak base. April restaurant and bar sales were 14% higher than in pre-pandemic April 2019, while March sales were 9% higher than four years ago.

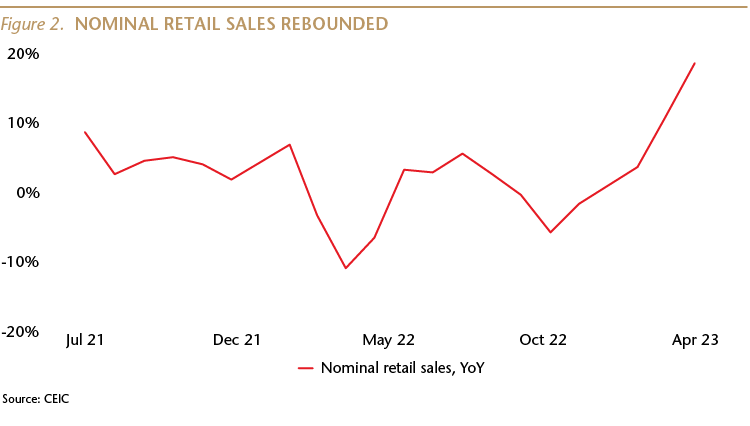

Growth of total, nominal retail sales (which includes sales of goods as well as food services) also came in strong on a YoY basis, rising 18% in April, beating the 11% rise in March.

The momentum of total retail sales did slow in April compared to March (and that slower pace of growth may continue for a while). The two-year compound annual growth rate (CAGR) was 2.6% in April vs. 3.3% in March. Overall retail sales in April were 14% higher than in April 2019, down from a 19% increase in March.

Looking deeper into the retail sales data we can see that some sectors performed well in April. Sales of sporting goods were 174% of April 2019 levels; sales of cosmetics (132% of April 2019), and gold and jewelry (124%) also were strong. The weakest categories were home furnishings, as well as electronics and appliances, but even those registered sales at more than 75% of pre-pandemic levels.

The slower growth rate of overall consumer spending in April is, in my view, a reflection of a cautious recovery in consumer sentiment after more than a year of COVID trauma, but does not lead me to believe the longer-term, consumer-led recovery is in doubt. I continue to expect the recovery in eating and drinking out to be followed, over time, by a recovery in spending on more expensive goods.

Property isn’t as bad as many think

Let’s move on to the residential property sector, where I think there is too much angst among investors.

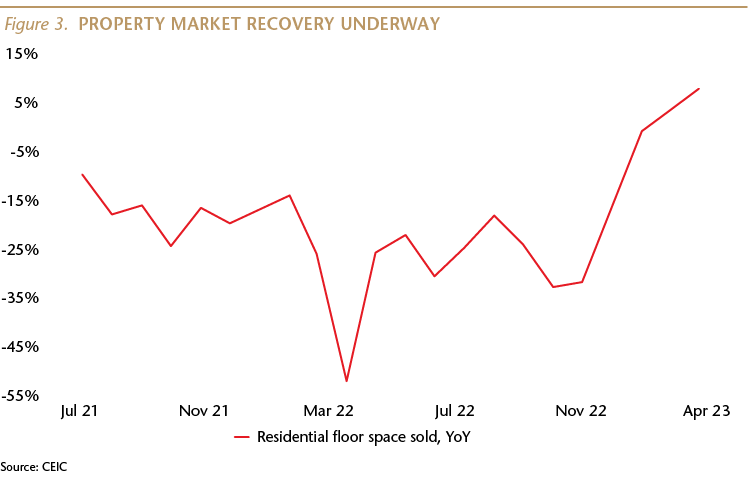

At the start of the year, I anticipated that new home sales would not begin to recover until the second half of this year, but this too has exceeded my expectations.

In the first four months of this year, new home sales on a square meter basis were equal to 90% of sales during the first four months of pre-pandemic 2019.

On a YoY basis, new home sales continued to accelerate in April, up 8%, following a 4% rise in March, vs. a decline of 52% a year ago.

Compared to pre-pandemic levels, the growth rate of new home sales did slow in April, with sales (on a square meter basis) equal to 62% of sales in April 2019, compared to sales in March that were equal of 94% of sales four years ago.

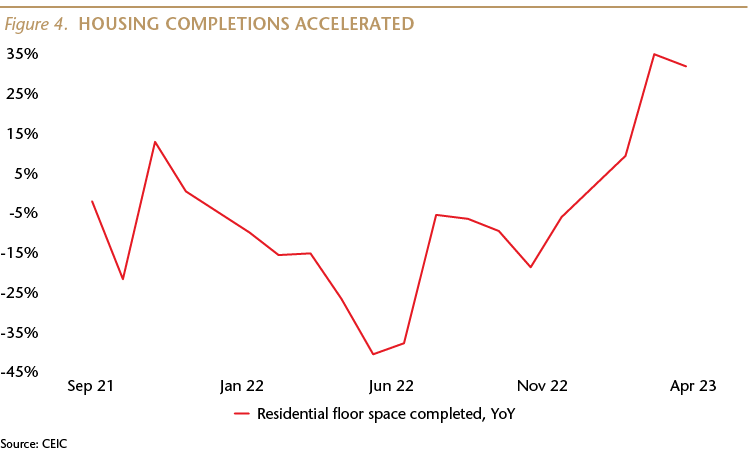

Housing completions continued to improve, up 32% YoY in April after a 35% rise in March. New starts, however, have been soft, as developers work through inventory.

The average price of a new home rose almost 11% YoY for the first four months of this year, partly because a higher than usual share of sales came in larger, more expensive cities. The average selling price today is 1% higher than two years ago, 31% higher than five years ago, and is up 65% compared to a decade ago.

It is worth acknowledging that China is past peak property. But this isn’t a new or troubling development.

The CAGR for new home sales on a square meter basis has been slowing for many years, as China’s housing market has matured. The CAGR for new home sales was 23% for the period 2001-2007, then 10% for 2008-2010, then 7% from 2011-2017, and down to 2% during 2018-2021. Despite this deceleration, and COVID, China’s GDP expanded at an average annual pace of 6.2% over the last 10 years.

Three significant challenges

While I am optimistic, I want to highlight three significant economic challenges.

The first two are related: industrial output and private-sector investment were both weak during the first four months of the year, with neither bouncing back as strongly as consumption. Contributing factors were softness in new home starts and car sales.

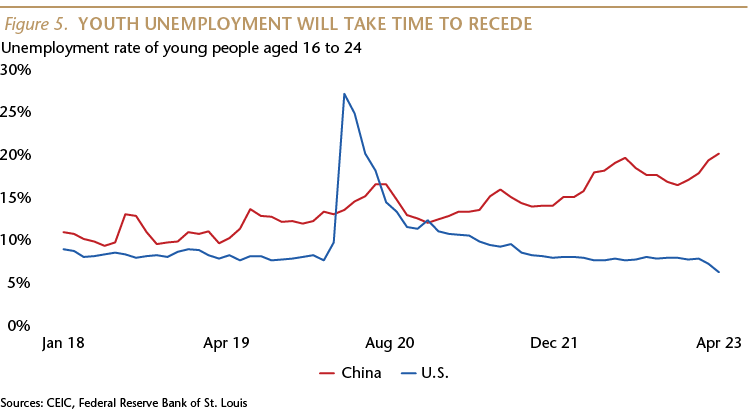

Weak industrial activity and private investment contributed to the third challenge: the unemployment rate for urban youth (16-24) rose to 20% in April from 18% in February. This is the highest rate since the government began reporting this data in 2018.

Given that the unemployment rate for migrant workers was only 5% in April, a bit lower than in March, the real problem is probably among recent college graduates.

Private firms—which account for about 90% of urban jobs—have been slow to regain enough confidence to invest and hire, and the global tech slowdown has led to job cuts in China as well. As many as 30 million services jobs were lost during zero-COVID, and the rehiring pace has been gradual.

On top of that, the number of university graduates is expected to be over 11 million this year, up from 7 million a decade ago. The Chinese economy has long struggled to generate enough jobs that match the expectations of new grads, who faced a significant challenge to gain a university place.

High unemployment for these people is a problem, and is likely to remain so for many months, but these are China’s elite, and they are unlikely to express their frustration on the streets, which would jeopardize future employment prospects. Government policies that encourage state agencies and state-owned companies to hire more young people, as well as continued recovery in services jobs, may mitigate this problem in the coming months.

Serious stimulus not on the horizon

At this point, the government doesn’t seem seriously worried about any of these problems and is sticking with moderately accommodative monetary and fiscal policy, as well as saying they will back off the recent regulatory crackdown to get out of the way of companies. Government economists told me that they don’t expect activity to fully return to pre-pandemic levels until the second quarter of next year. They do not anticipate a serious stimulus unless this process is clearly stalled.

The nascent recovery is likely sustainable

There are several reasons to believe that the gradual, consumer-led recovery is sustainable.

First, consumers have the means to spend. There was a 3.8% YoY rise in real (inflation-adjusted) income in the first quarter, the fastest pace since the second quarter of 2022. Consumer spending and confidence is also supported by the 59% rise in family bank balances from the start of 2020, as Chinese households were in savings mode during zero-COVID. The net increase in household bank accounts is equal to US$6.9 trillion, which is greater than the GDP of Japan in 2022, and equal to 118% of China’s 2019 retail sales. This is significant fuel for a continuing consumer spending rebound, as well as a recovery in mainland equities, where domestic investors hold about 95% of the market.

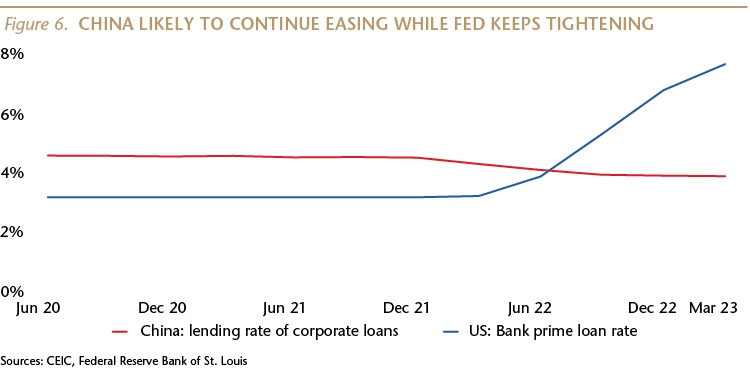

Second, China’s central bank is likely to continue easing while much of the rest of the world is tightening.

Third, Chinese companies and consumers are resilient, and the government is pragmatic. They have faced huge challenges since I first visited the country as a student in 1980, but they have continued to prosper. Per capita income rose 148-fold between 1980 and 2022, compared to a five-fold increase in the U.S. and seven-fold increase in the UK (all in nominal, local-currency terms).

The literacy rate for adults in China rose to 97% from 66%, and the number of college graduates rose to 11 million from 0.15 million. The homeownership rate rose to about 90% from about zero, and the infant mortality rate fell to 5 per 1,000 live births from 47.

During the last 10 years, while Xi Jinping has been head of the Chinese Communist Party, real per capita income rose at an average annual pace of 6.2%, compared to 1.4% in the U.S. and 1% in the UK.

U.S.-China relations: strained, but crisis unlikely

The political relationship between Washington and Beijing is likely to remain strained, but a crisis is only a medium-level risk, because I expect both Xi and Joe Biden to be pragmatic, and to recognize that a further deterioration in relations would be detrimental to each of their economies, as well as to their political prospects.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen recently stated that the Biden administration seeks a relationship with China “that fosters growth and innovation in both countries,” because the two “are deeply integrated with one another.” She said that the two nations “need to find a way to live together and share in global prosperity,” and that the U.S. does “not seek to ‘decouple’ our economy from China’s.”

Chinese foreign minister Qin Qang said, “A healthy, stable and constructive Sino-U.S. relationship is not only beneficial to both countries, but also beneficial to the world.”

During my recent trip to Shanghai and Beijing, everyone I met with expressed concern about the deterioration in the bilateral relationship, and they all said they hoped it improves. I didn’t meet anyone who preferred conflict or who expressed anti-American views.

Finally, political and trade tensions are unlikely to disrupt the Chinese economy, as domestic demand is its primary growth engine.

Andy Rothman

Investment Strategist

Matthews Asia